As good as new?

“The bacteria create a kind of scar tissue. Exactly how close this comes to regeneration, depends on the material,” says Harbottle. “As limestone has plenty of calcium and carbonate available, it’s likely that some of the newly formed calcite contains minerals from the original material ‘rearranged’ by the bacteria.”

According to Harbottle, the resulting fix is probably very similar to the original material, regaining its properties, such as strength and weather resilience.

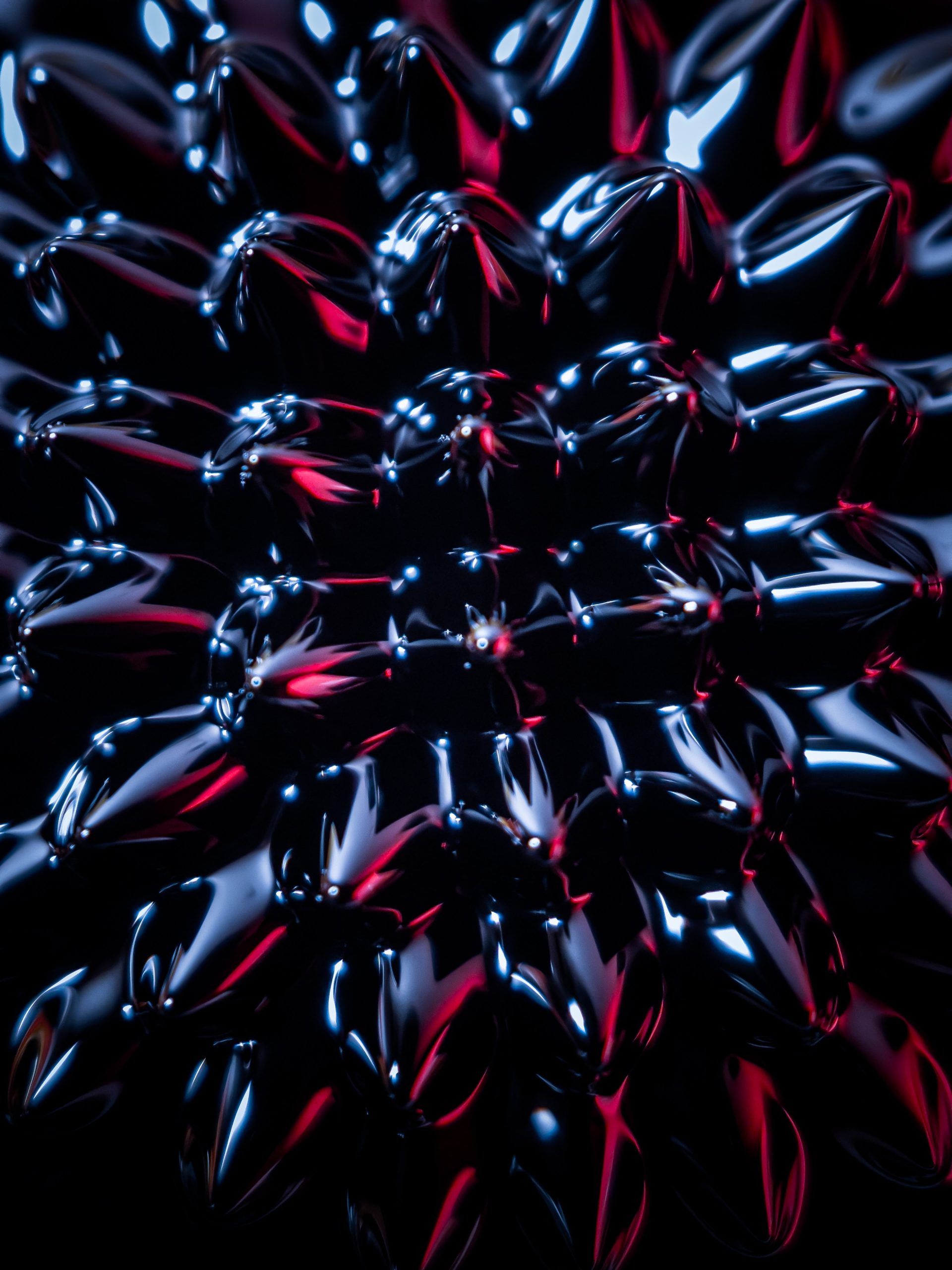

As Harbottle points out, self-healing as a concept has been widely applied to other materials, including polymers and asphalt, as well as concrete. “I believe it’s also been investigated in metals but this wouldn’t involve bacteria, which is most appropriate in construction materials as these involve mineral-producing processes,” Harbottle adds.

While Harbottle didn’t want to stray too far from his own area of expertise, he did allow a peek into the potential future of smart building materials. “Before an organism can self-heal, it first has to know that it is injured. So recent work in the United Kingdom has explored sensing and actuation systems – giving materials the ability to detect deterioration, analyse options and then decide what to do, without human intervention,” he expands.

“In the future, it could be possible to develop entirely autonomous self-repairing systems, but they would have to harvest the chemicals and energy necessary to produce a repairing agent from their surrounding environment.”

So when will our high street be self-repairing?

Currently Harbottle’s bacterial-driven solution faces a number of challenges. One is supply – Harbottle’s bacteria were sourced from his lab, but for mainstream use, indigenous bacteria would have to be sourced in large quantities, and would have to be trialled before use. Another limitation is demand.

The construction industry is rightly conservative when it comes to new materials, given the potentially devastating implications of failure. As Harbottle points out, there are not only safety risks but also aesthetic risks for heritage restorations.

“We need to build up – pun intended – evidence across a range of structures to win the confidence of potential users. Probably first prioritising non safety-critical environments or non-structural, cosmetic elements such as paving or facades,” adds Harbottle. Click here to find out more about Harbottle’s research: Bioengineered ‘self-healing’ for sustainable building and smart heritage preservation.

Source: CORDIS

Leave a Reply